In this report from IPS, Aline Jenckel interviews, TOM B.K. GOLDTOOTH, executive director of the Indigenous Environmental Network.

UNITED NATIONS, May 9, 2012 (IPS) – For centuries, indigenous peoples and their rights, resources and lands have been exploited. Yet long overdue acknowledgment of past exploitation and dedicated efforts by indigenous peoples have done little to end or prevent violations of the present, stated indigenous leaders in the Manaus Declaration of 2011.

The declaration, part of preparations for the upcoming U.N. Conference on Sustainable Development, frequently referred to as Rio+20, in June, recounted the “active participation” of indigenous groups in the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and similar efforts in 2002 that led to the adoption of the term “indigenous peoples” for the United Nations (U.N.) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Despite this work, “the continuing gross violations of our rights…by governments and corporations” remain major obstacles to sustainable development, the declaration continued. “Indigenous activists and leaders defending their territories still continue to be harassed, tortured, vilified as ‘terrorists’ and assassinated by powerful vested interests.”

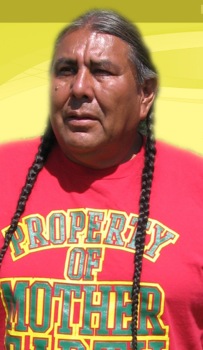

As Rio+20 approaches, IPS interviewed Tom B.K. Goldtooth, who has been an activist for social change in Native American communities for more than three decades and is the executive director of Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN), an alliance of indigenous peoples that combats the exploitation and contamination of the earth and will participate in the Rio+20 conference.

Goldtooth called for a “new paradigm of laws that redefine humanity and its governance relationship to the sacredness of Mother Earth and the natural world”.

The activist explained that the most effective measures for reducing deforestation, protecting the environment from unsustainable mineral extraction and preserving a better world for future generations are to strengthen international, national and sub-national frameworks for collectively demarcating and titling indigenous peoples’ territories.

U.N. Correspondent Aline Jenckel spoke with Tom Goldtooth about the main threats faced by indigenous peoples and how the Rio+ 20 conference could be a success.

Q: At the Rio+20 conference in June, you will speak on behalf of indigenous peoples and their human rights, in terms of protecting their natural environment and creating sustainable development. What is the key message you hope to convey?

A: The thematic discussion of green economy and sustainability creates differences in views between the money-centred Western views and our indigenous life-centred worldview of our relationship to the sacredness of Mother Earth.

Many of our indigenous peoples globally are deeply concerned with the current economic globalisation model that looks at Mother Earth and nature as a resource to be owned, privatised and exploited for maximised financial return through the marketplace.

With this development model, indigenous peoples continue to be displaced from their lands, cultures and spiritual relationship to Mother Earth, and destruction to the life-sustaining capacity of nature and the ecosystem that sustains us and all life continues as well.

For the sake of humanity and the world as we know her, to survive, there must be a new paradigm of laws that redefine humanity and its governance relationship to the sacredness of Mother Earth and the natural world.

This includes the integration of the human-rights based approach, ecosystem approach and culturally- sensitive and knowledge-based approaches. The world must forge a new economic system that restores harmony with nature and among human beings.

We can only achieve balance with nature if there is equity among human beings.

At Rio+20, global governments must look cautiously at any green economy agenda that supports the commodification and financialisation of nature and take concerted action to initiate the development of a new framework that begins with a recognition that nature is sacred and not for sale and that the ecosystems of our Mother Earth have jurisprudence for conservation and protection.

Full recognition of land tenure of our place-based indigenous communities are the most effective measures for protecting the rich biological and cultural diversity of the world.

Q: What are the biggest threats to Indigenous people’s livelihoods today, and how can they be addressed?

A: Indigenous peoples from every region of the world continue to inhabit and maintain the last remaining sustainable ecosystems and biodiversity hotspots in the world.

Destructive mineral extractive industries continue to encroach on indigenous peoples’ traditional territories. Unconventional oil and extreme energy development, with the real-life effects of climate chaos, are directly affecting the wellbeing of indigenous peoples from the North to the Global South.

Indigenous peoples can contribute substantially to sustainable development, but they believe that a holistic framework for sustainable development should be promoted.

With the knowledge that development that violates human rights is by definition unsustainable, Rio+20 must affirm a human rights-based approach to sustainable development.

Particularly, the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples must serve as a key framework which underpins all international, national and sub-national policies and programs on sustainable development with regard to indigenous peoples.

Q: Recently, some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) expressed deep concern about the reversals on agreements made by governments in 1992 and say there’s no country taking leadership of or acting as a visionary role in the conference. Do you believe there is still hope for new, binding commitments?

A: Because of the climate chaos, financial instabilities and ecological devastation, the world doesn’t have an option to reverse the agreements made in 1992.

World leaders must remember the active participation of indigenous peoples in the Rio Earth Summit (UNCED 1992) and the parallel processes indigenous peoples organised, which resulted into the Kari- oca Indigenous Peoples’ Declaration.

Agenda 21 embraced the language of Kari-Oca that recognised the vital role of indigenous peoples in sustainable development and identified Indigenous Peoples as a Major Group. Rio+20 must reaffirm the commitments made by UNCED to indigenous peoples in 1992.

(END)

Pingback: Rio + 20 : Montreal student Jessica Magonet heads to conference | LEARN FROM NATURE

It seems to me that we are even trapped by language in our effort to accurately describe relationship to land. Whereas Tom wears a t-shirt declaring “property of mother earth, Aline Jenckel re-interprets him to mean what is needed is “collectively demarcating and titling indigenous peoples’ territories”.

There may be other ways to understand “title” and the possessive “peoples'”, but both of these are generally understood as indicating ownership. This is the antithesis of what Tom seems to want to say.

Those of us who are now very disconnected from the land as mother have no perspective from which to begin to understand this reality, let alone be sensitive enough to be able to propose a solution. At best, land rights are seen as quaint cultural notions which, if acknowledged at all, must conform with “ownership” in order to apply in this modern world. Indeed Tom’s cultural understanding is effectively negated by applying titling, which over time inevitably transforms the culture into one which believes in ownership – a sort of genocide by osmosis.

Estoy muy de acuerdo en todo…desde niño me sentí muy unido y parte de la naturaleza; me asusta ver cómo se destruye y explota. Me incomoda cuando se discrimina entre indígenas y no-indígenas…yo también me siento indígena y nativo, aunque no pertenezco a una etnia definida y desconozco el origen de mis ascendientes, que considero irrelevante. Lo importante es que pertenezco a este mundo y me interesa lo que pasa en él.